My health is fine but the health of Parliament is not. I feel like resigning.

– LK Advani, 15 December 2016

The Indian Parliament, the Sansad, is the executive abode of the highest tier of legislative officials. This holy sanctuary of debating has been subject to ruthless, deliberate disruption of proceedings. From immature attempts to gain publicity, to mud-slinging and on-the-face slandering, the Parliament has witnessed it all. The present-day situation does not look exceptionally bright; for it wears the same dull grey of reminiscence of the yesteryears of parliamentary disruption. This phenomenon of stalling the Parliament to push forward demands is downright wrong and immoral: a manner of lackadaisical etiquette by elected representatives of the people should be tantamount to a criminal offence.

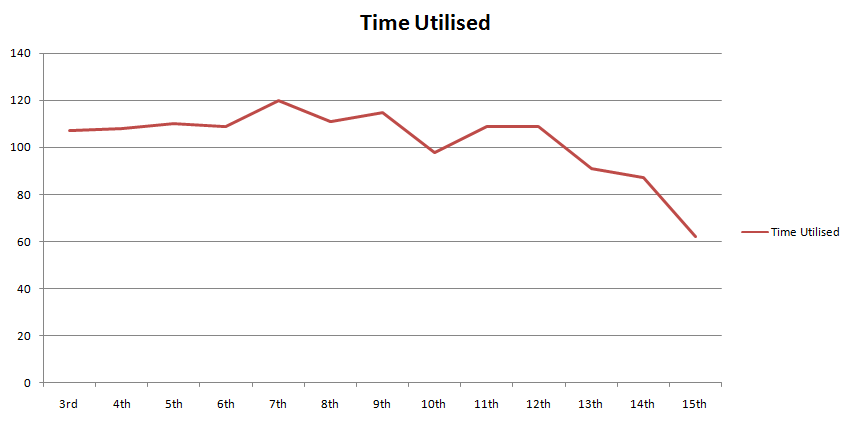

Making an approximate estimate, if all the three sessions of the Houses of Parliament are put in order, then it effectively functions for one hundred days a year. According to data put out by the Lok Sabha secretariat, the seventh session of the Lok Sabha under the iron lady, Smt. Indira Gandhi was the most productive, accounting for 120% of the assigned Lok Sabha time worth of constructive debating. What is disheartening, however, is the fact that this consistent record of constructive debating time has now degenerated into a slump that only sees a steep downfall. As per the following graph compiled from official data, it is evident that the last session of the Lok Sabha was the worst of the lot, accounting for only 62% of the time being used for work. The Lower House could not function for the rest of the allotted time due to disruptions and repeated adjournments.

Even on discounting items that are difficult to impute costs to (free petrol, subsidies, telephone calls, and much more), the daily expenditure of Parliament sits at a whopping cost of Rs. 2 crores. Hence, each Parliamentary minute is worth Rs. 2.5 lakhs. The exchequer bears this burden to facilitate smooth conduct of legislative business for the betterment and welfare of the nation. These costs are indirectly paid for by the common man on an individual level in the form of taxes levied at different junctures. Hence, if the stakes are so high, should the Members of Parliament not be accountable to the public for the work they do in the Houses of Legislature? Should the members who serve as repetitive impediments to the functioning of the Lok Sabha not be subject to automatic disqualification? Is it not economically unsustainable to harbour such disinterested people who find pleasure only in deterring the chamber of Indian legislature?

It is important to remember that while the Parliament does lose out on a considerable amount of moolah that could have been preserved, a stalemate condition also hampers the probability of taking the country forward, one step at a time. The Modi government, ever since its inception, has pointed to the need to improve the work culture and an emphasis on indigenous industries. Under the tagline Make in India, he has been successful in attracting investments. This dynamic influx of new investments and the ever-changing economic terrains require vigilant watch and effective laws that are devoid of fatal loopholes. Such laws that need to be put into effect pan-India can only be deliberated upon by the Union Parliament.

Disruptions in Parliament are now a result of cheap vendetta politics. Both the major players, the BJP and the Indian National Congress, are equally guilty of having resorted to such form of unwanted interference. During earlier years of the UPA regime, it was the BJP that had sought refuge in such unorthodox methods to derail the proceedings. Now, as fate would have it, the Congress is paying back the government in its own coin. Back in 2006, the veteran journalist and author Khuswant Singh lamented that the more he saw the Parliament conducting its ‘business’, the more he felt it was on the verge of collapsing. The authenticity of the statement would be applicable for years to come, given the trend of functioning.

This marked change in attitude to parliamentary proceedings must be analysed through pen and paper. It is definitely not easy to be in the boots of a Parliamentarian, and being cynical of such people is a very easy task to do. As is justified by general wit, the first few sessions of the Lok Sabha (1950-early sixties) observed heavy activity in legislative transactions. The time spent by successive sessions of the Lok Sabha has since mellowed down. The First Lok Sabha session devoted forty-nine percent of its time to the legislative business. Successive sessions till the eighth Lok Sabha ranged from twenty-two to twenty-eight percent (22%-28%) for the time dedicated to legislative work, with the Ninth Lok Sabha plunging to an all-time low of 16%. This reduction in legislative work can also be attributed to the emergence of the Cabinet form of government. The Cabinet, which essentially mirrors the Government elected, takes all of the decisions on the guidance of the Prime Minister. The Cabinet is in turn responsible to the Lok Sabha. This system was devised to render a smooth edge to the working of the Lower House.

Despite all the advantages that the Cabinet system may possess, it is rendered ineffective and useless if the Parliament itself does not function the way it is meant to be. This sanctum sanctorum of policy debating has been prone to attacks on its system of operation. Of what good is the Cabinet if there are no questions raised on the viability or need of a proposal? Questioning and defending bills are one of the most important tasks assigned to parliamentarians, and it should be their sacred duty to ensure that the sanctity of such a process is accorded its due respect. This provides the essence of democracy, a fundamental right of every Indian citizen.

As responsible citizens, it is definitely heart-wrenching to see the Parliament degrade into such low standards of operation unseen in previous years. It is my earnest hope that things take a turn for the good in days to come, as yet another session of the Parliament draws to a close. Twenty Sixteen has neared its death, and now it is time for Twenty Seventeen to bring in fresh hopes. The reprehensible divisiveness of party politics should not override the devotion of serving in the best interests of the country. It is our India, and only when we become mature enough to take the decisions for ourselves, dumping behind frail temporal loyalties, can we progress.