A Reversal of Fortunes

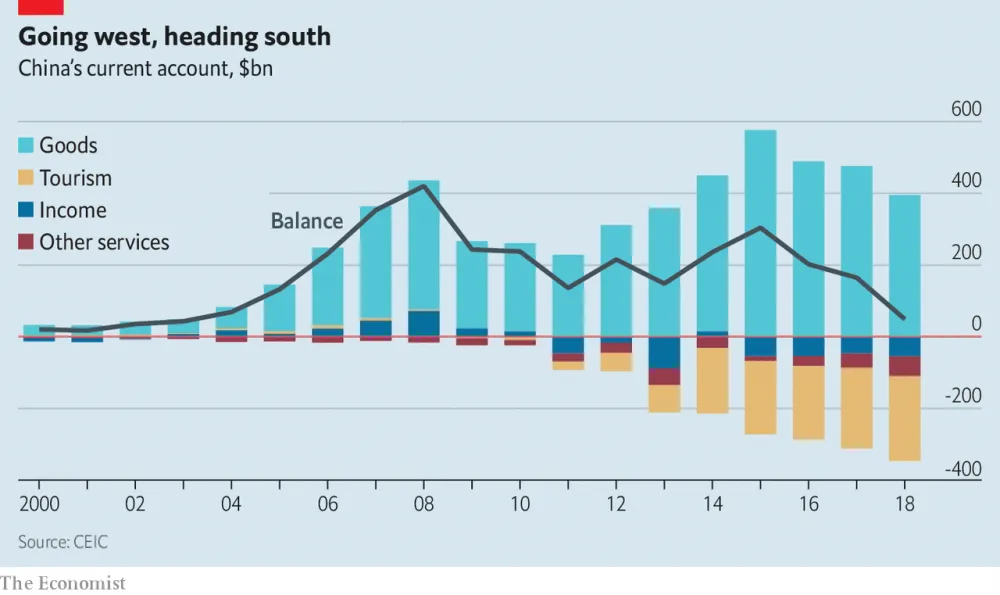

The fact that China has been a vociferous exporter and a tame importer of global goods may not come as much of a surprise. What hits hard, however, are the numbers behind the game. That ratio, disproportionately behemoth, was pegged at 127.16 (December 2018): which is to say, Chinese exports was a mind-boggling 127 times higher than its net import! All through these years, as an almost direct consequence, China has had an current account surplus. The time for merry-making may soon be running out; as China today faces the threat of racking up a current-account deficit for the first time in decades.

Analysts at global agency Morgan Stanley predicts China may face an imminent deficit in 2019, the first time since the last such deficit arose in 1993. This metamorphosis from a state of surplus, to that of a deficit, will bear an immediate cascading effect on both the Chinese economy, as well as State-run institutions. The Chinese model under Xi Jinping has become increasingly closed-door, with several accusations of skewed policy priorities for local competitors and expropriation of foreign-based technology. This shift might represent a rare willingness to jump over onto an era of economic liberalization, a perennially sore point between the interests of the United States and its Chinese counterpart.

Looking at the roots

Historical economic data makes it clear that China has saved way more than it invested. However, the working progeny of the yesteryear generation has almost an imbued tendency to splurge more. This is made clear by exponential increase in the consumption of smartphones, cars, and other luxuries. A report published by CEIC Data highlighted how Chinese tourists were the largest spenders abroad. In 2018 alone, China ran a $240 billion deficit in its tourism industry- its highest yet. This problem is only set to aggravate, as an ageing population draws down its savings, thereby further complicating matters.

A deficit in the year ahead will be negligibly small with respect to the Chinese GDP. Moreover, China has a sizeably good buffer of $3 trillion worth of foreign exchanges that could be used to head down immediate triggers of worries. This should give China time. What remains to be seen is what China does to revive its flailing mast. In April 2019, China is set to enter the Bloomberg Barclays bond index, which would help accelerate foreign funding into Chinese bonds to the tune of approximately a hundred billion dollars, all within two years. It has also eased quotas for foreigners who buy bonds, apart from luring pension and mutual funds who would now think about increasing their exposure to China.

Yet, on the reform front, moves remain limited. Restrictions for Chinese citizens were enforced in late 2017 on monetary withdrawal from Chinese banks overseas- and was capped at $15,000. While the official statement read that it was aimed at curtailing terrorism financing, money laundering and tax evasion, the fine print is not difficult to read this time around. China clearly has a sense of the upcoming perplexity. Such hardline State control may ultimately deter external investors from pumping their money into China, as it is uncertain if money once pushed in, can be taken out with ease. A system which treats locals on a higher ground than foreigners is not only conceptually flawed, but also smacks of corruption and instability.

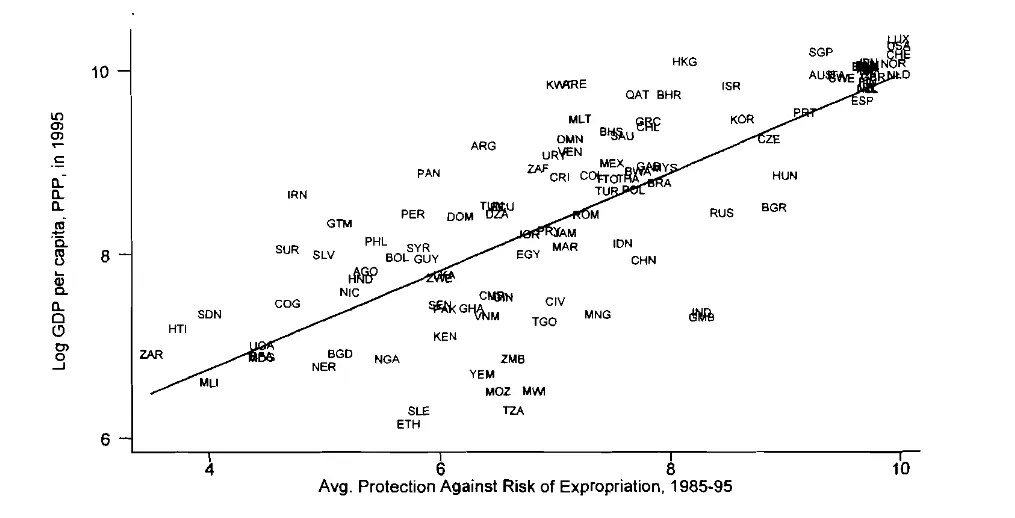

Economists Douglas North, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson have in a paper shown that the development of an open political system, aided by strong state institutions, help foster long run growth. While the West would inevitably want China to return to normalcy and develop institutions of global credibility, any such turn under Xi’s rule was out of question. In January, China reported that its economic growth cooled down to its lowest in twenty-eight years. This development is in line with the steep fall in exports, which fell an unexpected 4.4% in December 2018, along with a contraction in manufacturing activities.

Figure 2: A Graphical Representation of North, Robinson and Acemoglu’s work

of a linear relationship between openness of institutions and long run growth.

Figure 2: A Graphical Representation of North, Robinson and Acemoglu’s work

of a linear relationship between openness of institutions and long run growth.

Acute Debt Problem

On top of that, exists China’s humongous debt problem. China’s pile of $34 trillion dollar worth of public and private debt is akin to a ticking “debt bomb” to several economists. Among the forefront of such vocal critics is Arvind Subramanian, who brought out two pivotal pieces in Project Syndicate last year. Subramanian argues that China’s tactic of cooling down financial crises through increased State investment in domestic infrastructure projects only help embroils, or rather disguise, the mess that the debt represents. A near-normal economy that runs with a whopping 270% debt-to-GDP ratio is unarguably beyond the laws of economics. To put a benchmark reference, the Greek economy collapsed when debts reached 188% of the GDP. Stein’s law holds that if something cannot go on forever, it must stop. Yet, Chinese debts are on the roll. It has repeatedly tried to finance its domestic debt through external investment that reaps bountiful profits for China. The Belt and Road (BRI) initiative, that spans 68 countries and involves 40% of the world’s GDP, is one such attempt. Countries, however, are only growing aware of the increasingly compounded terms of such Chinese projects: even workers for those projects are of Chinese origin. Several countries have already cancelled Chinese projects due to high fiscal stress. The newly elected Malaysian Prime Minister Mathir Mohammed cancelled $22 billion worth of Chinese projects, which were passed by his predecessor Najib Razak, as such projects would be an added burden for Malaysia’s promising economic future. China’s loaning system is inherently biased, and to the extent that Harvard University’s Ricardo Hausmann recently termed it usurious.

The Road Ahead

On an overall front, the current fiscal year should be the year for undertaking structural reforms to the Chinese economy, to help it become more resilient against internal volatility and the threat possessed by an ageing workforce. This must be backed by political willpower, as such changes will help ensure benefits in the long run. The US-China trade war is only the fruit of a myopic vision on both ends: while China seems to resist liberalization on the front that it would seem pliable to western ascendancy, America’s continued persistence on the importance of a stable yuan over far greater concerns of a global slowdown as a result of the under-performance of the Chinese economy is upsetting.

It would be wise to recall Rüdiger Dornbusch’s law, which cautions that “the crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.”