Combating India's Population Problem

A national lockdown has brought to the forefront the immense neglect and sorrow lives that those at the bottom of the societal strata have to live. With several horrific tales of hunger, accidental deaths and a near partition-era exodus doing the rounds, it is natural to feel upset by the overwhelming stench of unimaginable hardships on countless men and women. On closer introspection, I realised that the root of the immediate crisis lies not only on the draconian lockdown alone but also on years of an exponential expansion of the population. The virus of population growth is as potent a threat as the present pandemic that has afflicted the world; if left unattended, this seemingly benign sore will metamorphose into a malignant one.

India's unchecked population surge has come to be a source of concern for many. With a landholding of only 2.41% and home to nearly 18% of humankind, India is beginning to reel from the severe stress its population exerts on it. While a youthful population is generally looked upon favourably, an excess of such a feature also carries with itself an array of perils. With increasing unemployment, inequality, starvation and a faltering economy amidst a host of other depressing issues, it is evident that India cannot afford to expand in terms of its demographic size any further. It is time to undo the vices of the past and implement family planning norms on a war footing, thereby paving the way for sustainable national development and growth in the decades to come.

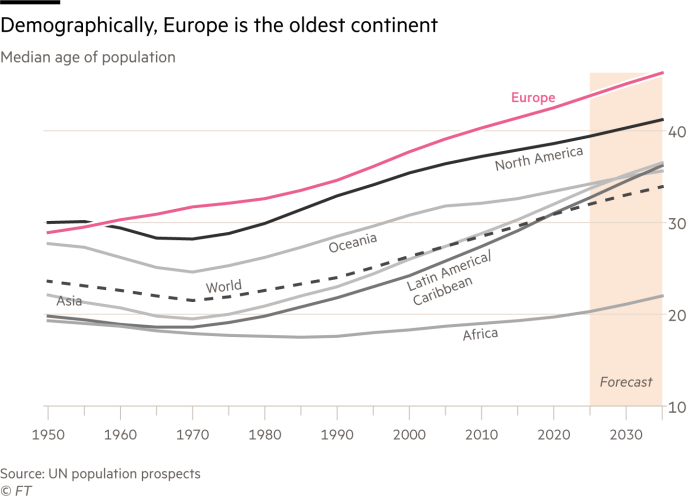

While the rest of the world is ageing, India has managed to retain its youth bulge. A youth bulge essentially points out that the young disproportionately outnumber the elderly in our country. The higher the figure, the better the productivity and national output rates. Much of the developed world order is progressively poised to morph into ticking time-bombs, with their workforce shrinking at a greater pace than those entering it. Europe is a classic case-in-point, with North America tailing behind. India, which has nascently entered a stage where it can reap the benefits of such demographic dividend, is hardly in a state today to encash on the bonus. The reasons are aplenty.

Our woes are on many fronts. Widening inequality has condemned the poor to remain fixated in poverty, while the rich have become more affluent. Joseph Stiglitz, in his book *'People, Power and Profits' *wrote that those born in poverty, often find it difficult to escape the vicious debt trap in their life span. Add to that a growing rural-urban gap, with massive influxes of migrant workers towards metropolitan and tier-one cities every year. Such trends have consequentially led to the establishment of migrant colonies clustered in unsanitary living conditions called slums. Mumbai's Dharavi is one such example. A combination of unfortunate factors has also pushed the average day-worker on the brink of starvation. The 2019 Global Hunger Index ranked India 102 out of 117 countries, which were evaluated on a three-indicator basis. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that malnutrition is equally rampant among the deprived. 37.9% of children below five suffered from stunted growth, while 14.5% of the population was undernourished, the report concluded.

Education and healthcare are like the two wheels of the chariot of sustainable growth. A humongous population count relegates education and skill-building onto secondary positions, as most are compelled to lend a helping hand to their family incomes at early ages due to ensuing poverty. In 2015, the school dropout rate was nearly 17%. In the age of Industry 4.0, only a handful are skilled enough to make careers out of their capabilities. The world's most prosperous countries have made a successful transition towards being knowledge economies, rather than being content with the tag of an assembler nation. The 2016 ASER report publicised much of the glaring loopholes of primary education across India. Hence, apart from bolstering investments made in the field of education in the short run, the long term idea should be to stabilise population growth and build intensively on the human capital we have then. This notion can also be extended onto healthcare; modern medical care is beyond reach for the deprived in India. Equitability in healthcare can only be brought about when population growth is considerably low and benefits of advancement can reach those who require it the most. It has been observed that the trickle-down economic theory- the idea which professes that a rising tide (read, development) shall lift all boats- does not hold good in populous countries.

On the policy front, the importance of family planning was realised even before independence was attained. In fact, in 1951, India became the first developing country to implement a state-sponsored family planning programme. The Radha Kamal Mukherjee Committee (1940) was one such pioneering venture, which was commissioned by the Indian National Congress to evaluate the chapter of population control. It was followed by the Bhore Committee (1943) and post-independence, was looked into by the Five-Year Plans prepared by the now-defunct Planning Commission. Yet, all of these committees and plans emphasised on self-control to curb further growth. As governments became increasingly concerned about the outcomes of such rapid spurts, in 1976, the National Population Policy was constituted. The NPP (1976) was radically distinctive from its precursors and advised incentivisation as the way forward to control the population. It noted, "... to wait for education and economic development to bring out a drop in fertility is not a practical solution. The time factor is so pressing, and the population growth so formidable, that we have to get out of the vicious circle through a direct assault upon this problem as a national commitment." Such a radical measure also led to experimental legislation on compulsory sterilisation, enforced during the emergency era, which ultimately ended in a fiasco and was rolled back. However, the viciousness with which the Union government combated the issue brought with it a fair share of the limelight.

A Statistical Overview

The above plot, sourced from Census estimates in 2011, clearly shows a negative relationship between population (independent test variable) and literacy (dependent variable). As population increases, a degradation in literacy rates is observed. Most of India's northeastern states have fared excellently well on literacy counts, and have significantly controlled their population growths. We can further expand upon this idea, if we take a look at Human Development Index (HDI) figures for Indian states (2018 UNDP data).

A polynomial-order decreasing trend line relationship was observed between Population and HDI. Theoretically, an HDI score of 1 indicates all-round development. HDI scores are based on the standard of living, literacy, and healthcare access. It is no surprise, again, to observe states with high HDI scores having a comparatively lesser population than those who fare poorly on their HDI scores. It is evident from the graphical visualisation that Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal are clear laggards when it comes to development and population control. Kerala and Goa serve as model states, with high HDI indices as well as a low population count. The final chart would attempt to illustrate the Total Fertility Rate (TFR)'s relationship with the Crude Birth Rate (CBR, per 1000 people) over the decades.

The above plot brings out the positive side of our efforts against combating the population menace. Over the decades, we have been successful in continually curbing the TFR and consequentially bringing down the CBR at the same time. It is in alignment with the vision of the National Population Policy (2000), which aimed to bring down the fertility rate to 2.1 by 2045.

A Way Forward

Clearly, not all is lost. The battle to reign in our population count has begun to be taken seriously at all levels in recent times. It was heartening to see Prime Minister Modi bring to spotlight the grave threat, labelling 'population explosion' as a challenge for the upcoming generations. He equated efficient family planning with patriotism, and openly called for state governments and the central government to act together over a long-term solution. However, it is not only an urge for chauvinism that should drive forward the momentum to bring in immediate reforms, but also economic profits. Ashoka Mody and Shekhar Aiyar's work at the IMF estimated the demographic dividend for India (the additional growth in per capita income due to demographic factors alone) for the next few decades, assuming optimal conditions to reap the benefits:

A two-child policy is also the need of the hour, apart from usual awareness drives initiated by the government. Assam was the first state to implement coercive disincentive tactic to solve the pestering problem, by denying government jobs to those with more than two children. The Union government may also adopt such a policy, but any such order should not be retrospective in nature. Simply put, any such disincentive should be applicable only for future applicants after a minimum period of nine months, so that prospective employees should make a concerted effort towards the governmental objective. Family planning measures are also heavily impacted by the standard of living. As more migration takes place from rural hinterlands onto urban metropolises, people will automatically regulate themselves to having a bare minimum number of children so as to meet the rising costs. Monetary incentivisation, in the form of tax benefits and other compensatory reliefs, shall go a long way to combat this vice in India.

We have no control over the world we inherit, but we have complete control over the world we leave behind. However, credits where due: the present dispensation does seem to actively view this as an immediate concern to be worked upon. Effective family planning measures, especially in a country as diverse and broad as India, shall offer our progeny a fair chance at living a life of dignity and bridge the inequality. Humankind will be on the slippery slope to hell unless we take stock of the birth rate on an urgent basis.

Machiavelli's words ring true today, exactly as he had prognosticated:

“When every province of the world so teems with inhabitants that they can neither subsist where they are nor remove themselves elsewhere… the world will purge itself in one or another of these three ways (floods, plague and famine).”

Niccolo Machiavelli