The importance of a robust national constitution in contemporary times cannot be understated. Constitutions around the world have helped shaped the modern polity that we find ourselves in. They have been surprisingly resilient and firm throughout several tribulations spread across the spectrum of contemporary history. Yet many more are crumbling by the day, their original intent and spirit being actively usurped by power-hungry authoritarians. In India, the Constitution has been described as a “living, breathing” document that testifies our commitment to building a progressive and democratic state.

The Comparative Constitutions Project is one such initiative that has been set up with an explicit aim to quantify Constitutions across the world in terms of certain predefined and widely accepted parameters. These include the pillars of an ideal free state: judicial independence, number of rights assured, and the degree of legislative and executive powers that the Constitution permits. Does the length of a Constitution alone help predict how free a country is? Does increasing executive power hamper judicial independence? In an effort to understand and frame definitive responses to several questions like these, I decided to perform an exploratory analysis on data available with the CCP Project. The following is a quantitative, mathematical attempt to break down how Constitutions shape a country, and if tweaking a parameter or two can yield desired results.

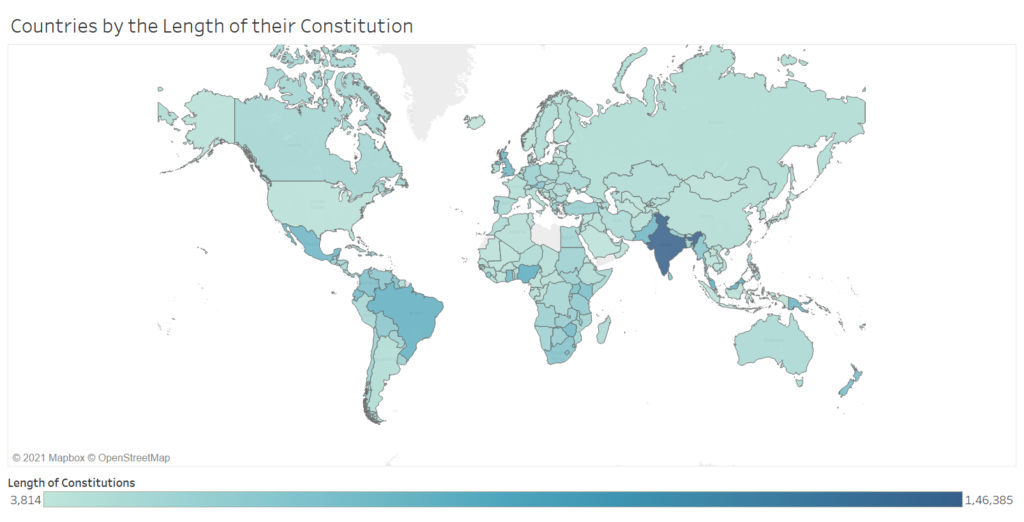

1. Countries by their Constitutional Length

Most of the countries that happen to have the lengthiest of Constitutions are also incidentally third-world countries. Perhaps the fear of delving into a state of chaotic anarchy compelled those who framed the Constitution to fill as many gaps and loopholes as could have been practically possible. The top-ten lengthiest constitutions of the world, in descending order are:

A choropleth map depiction makes it evidently clear that India stands out from the rest in terms of the sheer length of its Constitution. It encompasses varied subjects, including concepts and ideas borrowed from foreign constitutions, and defines the rights, roles and responsibilities of both the government and the citizen. In fact, India’s Constitution is more than twice as voluminous as its next competitor, Nigeria. Even Latin America features prominently as a bunch of countries with extensively detailed Constitutions.

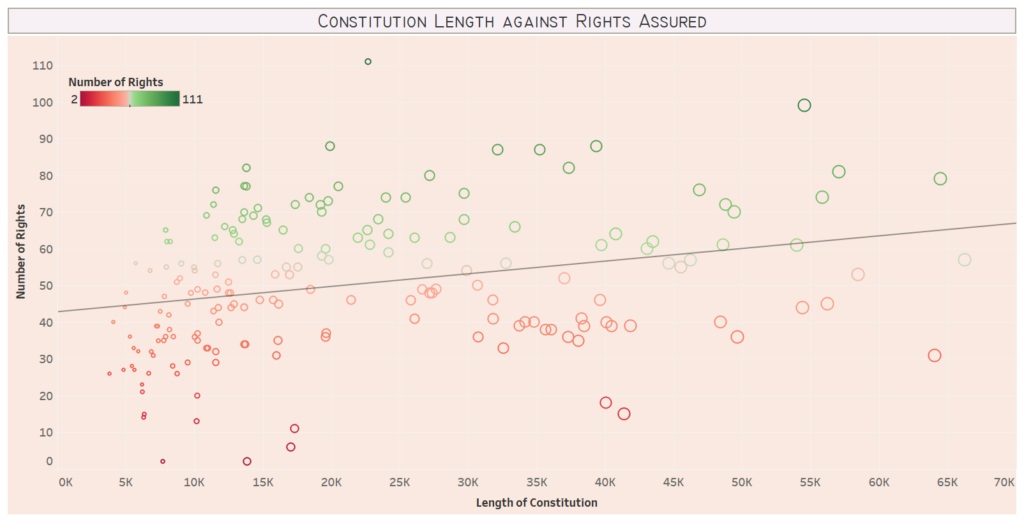

2. Constitutional Length and Rights Assured:

The Universal Declaration for Human Rights was a significant stride towards standardizing a globally accepted set of fundamental human rights that would enable an individual to lead a life of dignity. The Comparative Constitution Project (referred to as CCP henceforth) has analysed a set of 117 different rights found in national constitutions. The rights index indicates the number of these rights found in any particular constitution. In the following plot, we establish a relation between the length of a Constitution and the number of rights assured by it. We have excluded India from the analyses below because it is an outlier and does not otherwise disagree with the forecast trend.

| P-value: 0.0001278 |

| Equation: Number of Rights = 0.000344274*Length + 42.8475 |

Clearly, a linearly increasing trend exists for the number of rights against the length of the Constitution. The more encompassing a Constitution becomes, the greater the probability that it allows for the rights of its own citizenry. Those countries that fall below the trend line (marked in red) lag against other countries in terms of assuring a wider spectrum of rights.

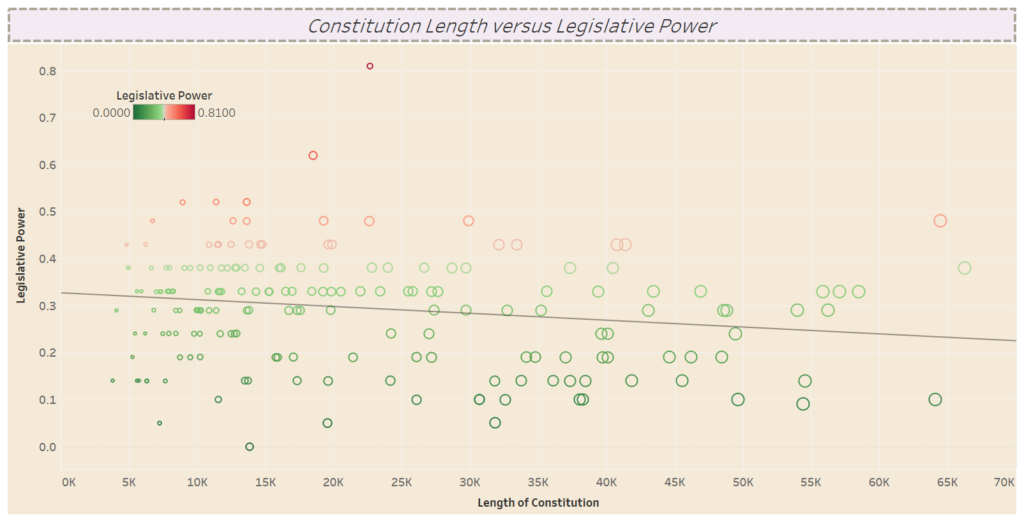

3. Constitutional Length and Legislative Power

This captures the formal degree of power assigned to the legislature by the constitution. The indicator is drawn from Elkins, Ginsburg and Melton, The Endurance of National Constitutions (Cambridge University Press, 2009), in which a set of binary CCP variables was created to match the 32-item survey developed by M. Steven Fish and Mathew Kroenig in The Handbook of National Legislatures: A Global Survey (Cambridge University Press, 2009). The index score is simply the mean of the 32 binary elements, with higher numbers indicating more legislative power and lower numbers indicating less legislative power.

| P-value: | 0.0131016 |

| Equation: | Legislative Power = -1.45739e-06*Length + 0.327069 |

We find a negatively sloped line as the Constitutional length varies against the Legislative Power of the country. This is indicative of greater checks and balances that have been introduced in such Constitutions that have an adverse effect on arbitrary legislation. While it is certainly a contentious issue in terms of bureaucratic red-tapism, greater oversight more often than not results in well-formulated legislation that goes on to have significantly more impact than their counterparts who do not have the benefit of consensus and elaborate discussion preceding it.

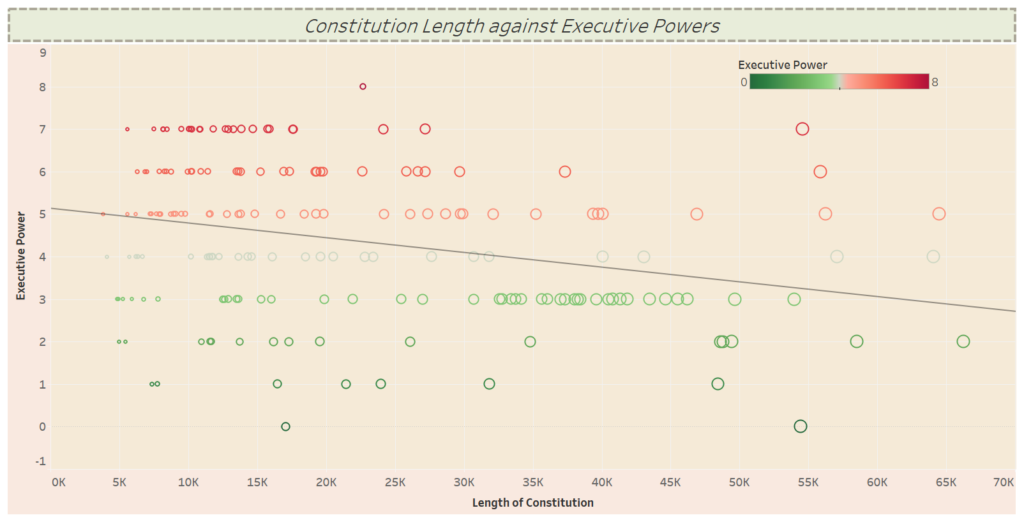

4. Constitutional Length and Executive Power

This is an additive index drawn from a working paper, Constitutional Constraints on Executive Lawmaking. The index ranges from 0-7 and captures the presence or absence of seven important aspects of executive lawmaking: (1) the power to initiate legislation; (2) the power to issue decrees; (3) the power to initiate constitutional amendments; (4) the power to declare states of emergency; (5) veto power; (6) the power to challenge the constitutionality of legislation; and (7) the power to dissolve the legislature. The index score indicates the total number of these powers given to any national executive (president, prime minister, or assigned to the government) as a whole.

| P-value: | < 0.0001 |

| Equation: | Executive Power = -3.46203e-05*Length + 5.13594 |

It does not defy our expectation that a lengthier constitution would naturally attempt to curb excesses on part of the executive. Here, the monotonically decreasing trend function has a higher R-squared value than the preceding trend function that evaluated the legislative powers against increasing Constitutional length. This means that the trend line is a better fit- and hence a better estimate- to prove the empirical relationship. With increasing Constitutional Length, Executive Power goes on declining. However, some exceptions still remain (marked in red), but they are found to have been significantly slumped in number post a certain threshold in the length parameter.

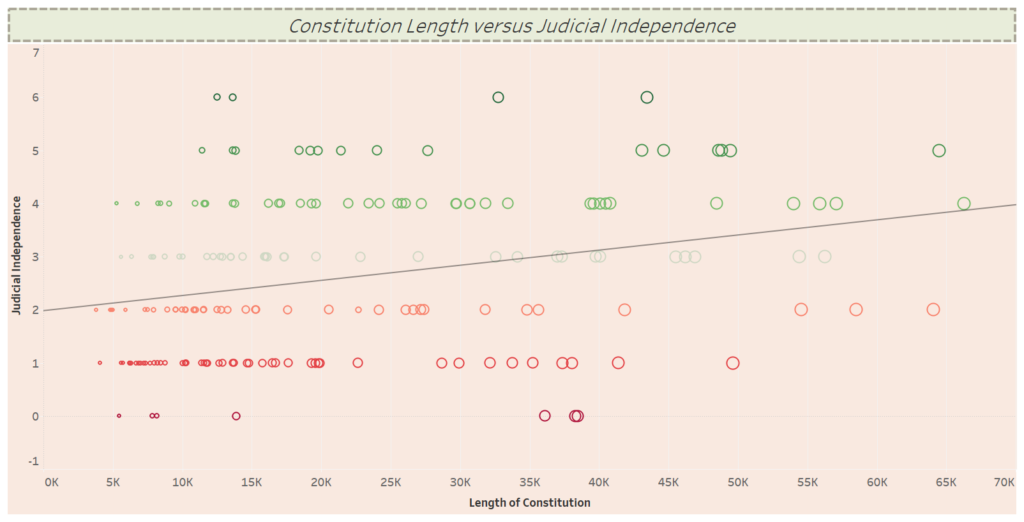

5. Constitutional Length and Judicial Independence

This index is drawn from a paper by Ginsburg and Melton, Does De Jure Judicial Independence Really Matter? A Reevaluation of Explanations for Judicial Independence. It is an additive index ranging from 0-6 that captures the constitutional presence or absence of six features thought to enhance judicial independence. The six features are: (1) whether the constitution contains an explicit statement of judicial independence; (2) whether the constitution provides that judges have lifetime appointments; (3) whether appointments to the highest court involve either a judicial council or two (or more) actors; (4) whether removal is prohibited or limited so that it requires the proposal of a supermajority vote in the legislature, or if only the public or judicial council can propose removal and another political actor is required to approve such a proposal; (5) whether removal explicitly limited to crimes and other issues of misconduct, treason, or violations of the constitution; and (6) whether judicial salaries are protected from reduction.

| P-value: | < 0.0001 |

| Equation: | Judicial Independence = 2.84882e-05*Length + 1.98147 |

It is heartening to note that judicial independence does tend to better itself if constitutions are more verbose. Judicial independence is considered as a cornerstone of a successful democracy. Thus, those countries lagging in terms of the aforementioned parameter must do more to ensure the protection of those in the hallowed institution of rendering justice; a corrupted justice mechanism only accentuates the decline of political power and foments resentment among all stakeholders involved.

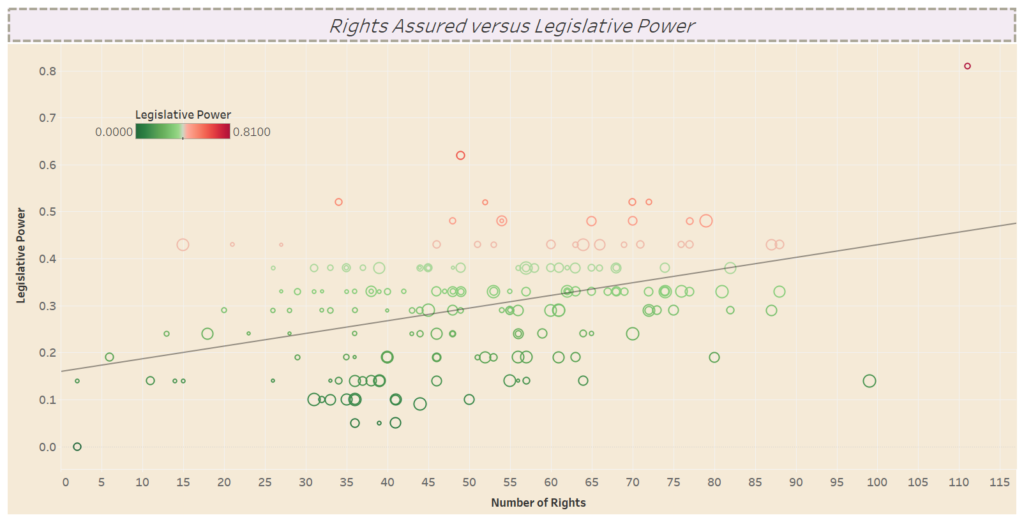

6. Rights Assured against Legislative Power

| P-value: | < 0.0001 |

| Equation: | Legislative Power = 0.00269629*Number of Rights + 0.159655 |

Now that we are done understanding the effect of a verbose Constitution on key parameters, it is also important to study the inter-relationships between these parameters themselves. Visual evidence from the plot suggests that if a country wishes to increase the number of rights it grants to its people, it must also make an effort to increase the legislative power. How is this consequential, then? Often, bolstering legislative power leads to overriding of the minority voice. A possible explanation for this observation is that legislatures all around the world tend to be on the conservative side, they mostly resist dramatic change wherever possible. Including legislation defining new rights often are results of landmark judicial interventions or extraordinary consensus to include a particular right as one guaranteed by the Constitution. Hence, only an emboldened legislature can make way for a broad range of new generation rights. For example, although experts have cautioned of increasing privacy woes and a landmark Supreme Court judgement that mandated the right to privacy (KS Puttaswamy v/s Union of India), the right to digital privacy has been languishing all along. It has managed to garner some attention now that corporations have begun consolidating their user bases, but it goes a long way to demonstrate how legislatures are normally not very welcoming of expanding the set of rights issued to its citizens.

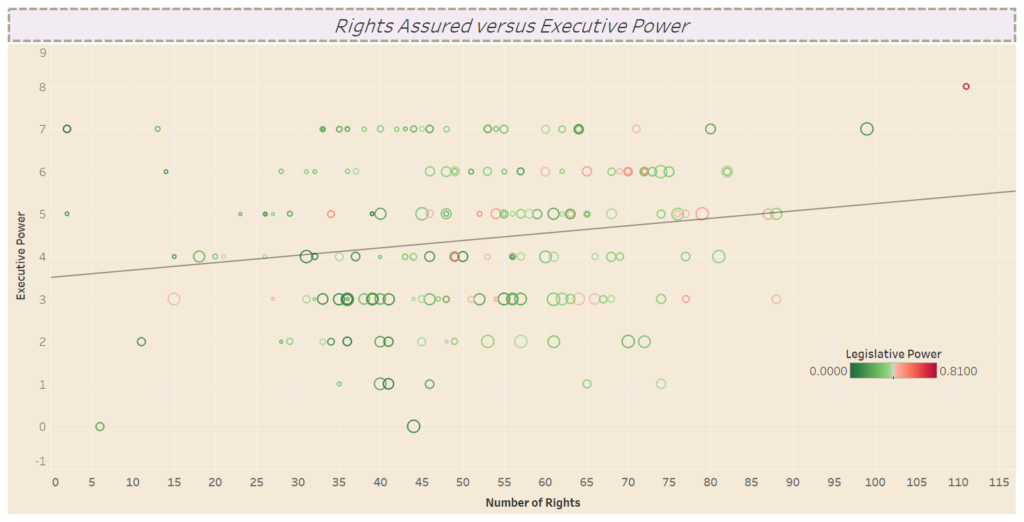

7. Rights Assured versus Executive Power

| P-value: | 0.0107787 |

| Equation: | Executive Power = 0.0173729*Number of Rights + 3.50851 |

As defined earlier, executive power alludes to the ability of those discharging Constitutional duties to enact sweeping changes without immediate clearances or review by oversight bodies. The trend is rather a surprising one, as an ideally free country should not require strong executive action to guarantee its rights. However, this is not the case. To have a greater degree of individual liberty and rights granted, it takes a strong executive. Multiple factors can be responsible for such a deviation from intuition, foremost among which can be a governmental determination to boost national standards and rankings in terms of freedom(s) granted and rights assured.

Concluding Thoughts

Much of our knowledge about the effectiveness of a constitution comes from our experience with the country implementing it. Can a constitution ever be truly quantified in terms of set parameters, and more importantly, can a model Constitution be defined by computing all past experiences and empirical relationships observed together as a gift for posterity? At present, it is difficult to say. The vagaries of ever-changing data in social sciences put researchers in a very uncomfortable position to entrust complete, unquestioned belief in one model alone. Thus, our understanding of the functioning of Constitutions can be bettered not only by objectively studying and assessing the documents alone but also by noting how well it is implemented and the laws it prescribes, followed.