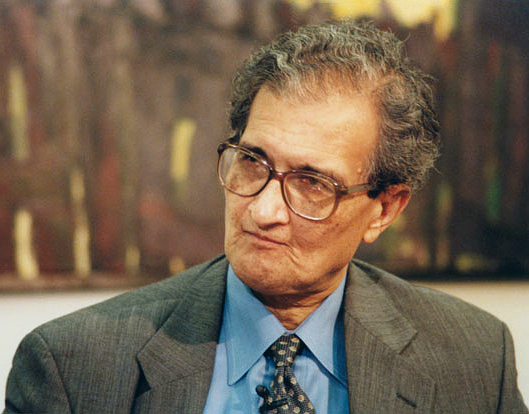

An unilateral thrust on the growth perspective (based on GDP figures alone) being central to the measure of human progress had led to a severely skewed society by the end of the 1980s. This was a phase where rapid de-industrialisation was met with hurried globalisation in the West; firms were growing ever larger; and markets were precipitously moving towards monopolistic tendencies. Economic disparities between the rich and the poor richocheted; and it was evidently clear that the ‘real wealth’ of a nation lay not in its present ascendancy, but in the development and building of the ‘human capital’, or intellectual resources. Amartya Sen, recipient of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, was rewarded for having pioneered the concept of the Human Development Index. What was so very remarkable about Sen’s work then, that changed the worldview on the idea of human development and societal progress by panoramic proportions?

A LOOK AT THE INDICES

The answer to the question requires a multi-pronged analysis into the factors that determine mankind’s advancement over a period of time. The Human Development Index (HDI), a score between 0 and 1, looks into the input variables of life expectancy, education and standard of living as determinants of the HDI score. A higher HDI index is reflective of a country that is substantially ‘developed’, in other words, a nation with a HDI score 1 indicates a highly sophisticated society that has a reasonably high average lifespan, good education standards and a fairly decent standard of living. The arrival of the HDI as a parameter helped governments around the world to engineer a transition from a singular focus on GDP-oriented growth policies earlier to the brand of welfare economics. The UNDP’s HDI Report 2018 ranks India with a score of 0.64 at the 130th position, which classifies it as ‘medium human development’.

HDI sensitised nations about the diminishing importance of income alone to adjudge the progress made by a country, yet, it was not enough to provide an exact idea of the scale of deprivation faced by the population. While most countries maintained some form of a record of poverty levels, these statistics did not signify much other than an income handicap. In 2010, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) collaborated with the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) to launch the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI)- a three dimensional overview into various factors resulting in true poverty. The MPI scale focuses on establishing trends of quantifiable deprivation amongst people across the world. The MPI also uses in broad sense, the same set of parameters that goes for calculating the HDI score- but it is more exhaustive in nature. While HDI calculation involves a single indicator for each dimension, the MPI calculation deals with respecting data from multiple sources from each applicable dimension. This is one cause for the MPI index being available for just over 100 countries, while the HDI index is almost accessible for every country today. While both the HDI and the MPI serve as fantastic indicators for societal development, critics have often slammed the indices for not taking into account the “moral, emotional, and spiritual” dimensions of poverty. The Global Happiness Index, conceptualised of late, is an attempt to correct that anomaly.

The World Bank in 2018 released a new report, titled the ‘Human Capital Index’. It expands on the idea that for sustainable long run growth in the future, nations must ensure considerable funds for the advancement in sciences and technology. Paul Romer, who shared the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economics, based his theory on economic growth with ‘endogenous technological change’- more is the number of people working in the knowledge sector, greater is the probability that the country is on the road towards prosperity. Incentivization of innovation, along with a increase in public spending on higher education and healthcare results in a workforce that is not only skilled, but also maintains higher productivity over the long run due to access to better healthcare facilities. In the inaugural report launched by the World Bank, India is ranked at the 115th position out of a total of 159 countries that were evaluated.

THE WAY FORWARD

The triad of development indices, namely the HDI, MPI and the HCI, have enabled policymakers to frame legislation that can over time, change the dynamics of an economy. These parameters are also a great aid for a nation to align itself with the UNDP’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). India, despite having the advantage of its demographic dividend (average age in India is only 29, with 65% below the age of 35), has mostly been ranked lowly in all the three indices. India’s mediocre performance on the rankings may look astonishing on first glance, but it is not impossible to dissect why. A nation teeming with almost 1.3 billion people will have a natural strain on its resources. The 2018 Oxfam report also brought to light how India’s top 1% possessed 73% of the national wealth- while the basal rung saw their fortunes rise by only 1% for the same year. In his book ‘People, Power and Profits’, Joseph Stiglitz argues that a person born under the curse of poverty has a very low prospect of escaping the poverty trap- indicative of the dampening consequences of widening inequality. The same is true for India. Rise of inequality, coupled with poor grassroot-level implementation of developmental programmes, have reared their ugly head as a draconian duo- a true malaise for an otherwise aspirational population.

The glaring fault-line lies in the fact that despite heavy investments being laid out for the infrastructure sector, very little ground has been covered when it comes to providing education to our children. While universal access to education has been mostly achieved, the concern about the quality of education is very much valid. The Annual Status of Education Report (2016) highlights several of these loopholes. It brings to light how the proportion of children in fifth grade, who can read a book of second standard, has declined to 47.8% in 2016 from 48.1% in 2014, amongst several other mostly depressing statistics.

Similarly, despite a renewed vigour to improve on our medical infrastructure, our healthcare system remains in a deplorable state. Ayushman Bharat, a mega-healthcare insurance system on the lines of America’s famed ‘Obamacare’, was driven to the hush primarily because despite having established government hospitals all over India, the quality of services rendered in such hospitals were nowhere in comparison to those doled out by speciality private sector medical institutions. Positive mends are being made only of late, with induction of more seats in medical colleges for doctors an encouraging move.

For India to establish itself as a world leader in sustainable growth, it must start investing heavily to promote its research and development institutions. India’s current spending in R&D, as a proportion of its GDP, is a

The benefits of such heavy investment may present themselves as unwarranted expenditures to the right-wing, but it is to be remembered that a nation can only go as far as its people can. It is thereby without doubt, in the greater interests to sanction funds that help solidify the dream of a secure future, not only for us- but also for generations ahead.