They say that it is a heyday for conspiracy theorists when they perceive the world order to be in an anarchical state. COVID-19, primarily originating from the industrial town of Wuhan in China, has now captured the attention of the world’s best minds as much as the multitude alike. With a staggering count of over three million infected and over two hundred thousand fatalities, the act of discounting the threat from this invisible virus would be nothing short of imbecilic. Nature’s most social animal now needs to confine himself within the four walls of the home.

At this hour of adversity, outrageous claims have flooded the public domain, with opinions ranging from anything as grave as biowarfare to toned-down claims of divine punishment for humanity’s sins. Further complicating the matter are calls for cutting down on the WHO’s budget- thereby derailing efforts to provide aid where ever it is most necessary. Every single worker, corporation and institution has to bear the wrath of the rampage trail that the virus will leave behind. In the next few years, we may have to radically alter our lifestyle to stay off the radar of the disease. COVID-19’s impacts are anything beyond that of a petty trade war or an experiment gone astray; it holds immense sway and influence over the geopolitics of the land that is soon to follow once the situation subsides. This essay is an attempt to debunk such claims and examine each such observation on its merit.

Debunking Myths

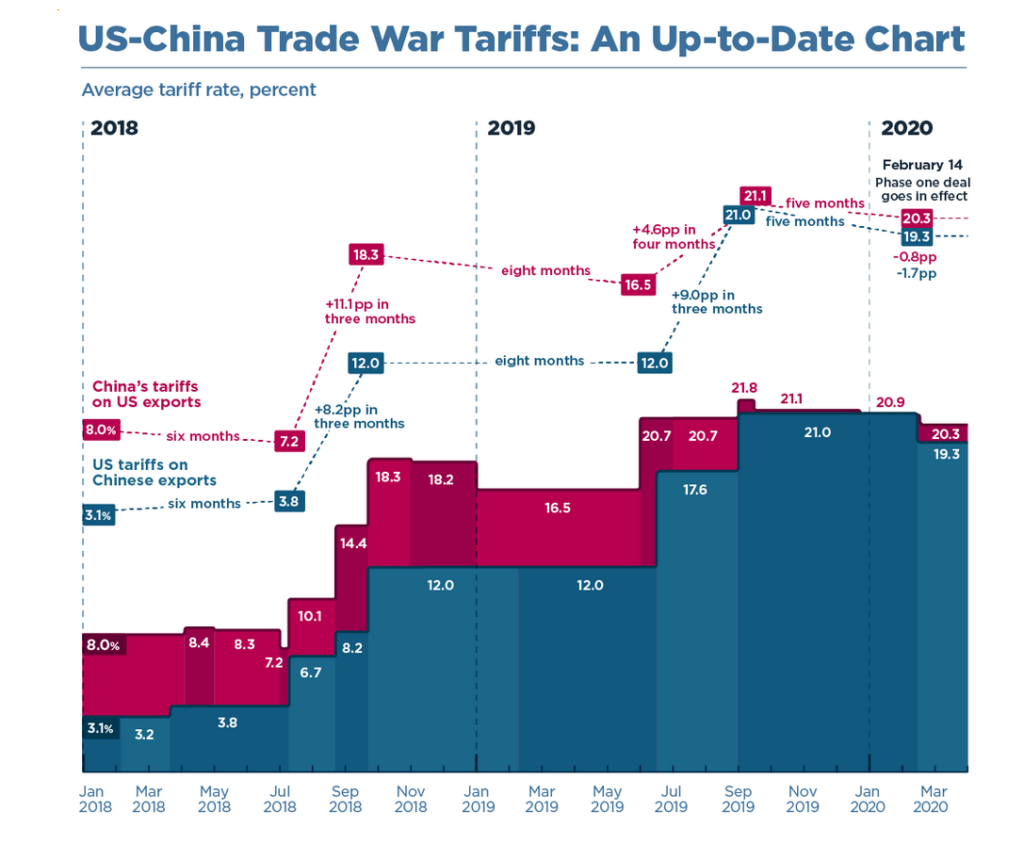

The United States and the People’s Republic of China are engaged in a bitter trade battle ever since mid-2018. The American President grew increasingly distraught by the States’ growing trade imbalance with China, and accused Chinese officials of complicity in unfair trade practices and violation of intellectual property rights. In June 2018, Trump announced a 25% tariff on Chinese imports worth $34 billion and proclaimed a slew of cesses on other imports worth $16 billion. Till date, the US has slapped hefty import fees on Chinese goods totalling a sizeable $360 billion. In China, anti-US sentiments were quick to grow; they realised the move as an attempt to throttle the Chinese ambition for economic ascendancy. In retaliation, China imposed higher import duties on American goods worth $110 billion. As China delivers many key raw materials, a rise in import costs disrupts supply chains, thereby making products dearer. The US also hurt Chinese interests indirectly by blacklisting telecom major Huawei on flimsy grounds of national security and bullied allies into doing the same by threatening them with duties.

With China’s interests and fortunes swiftly heading south, many observers have remarked that the emergence of a novel coronavirus- that results in severe respiratory difficulties and in some cases, even death- is a ploy by China to halt the pressure tactics employed by the US. They remark that it is a diversionary tactic used by the Chinese administration to shift attention to domestic affairs, thereby providing China the necessary time to work upon its strategic interests. The fact that China has tamed the pandemic significantly quicker (critics being fully aware of the notoriety of Chinese data repression), and the US taking the hardest hit, have aroused the suspicion of foul play by many. The obvious futility of the claim stands out. The novel coronavirus has not discriminated its victims by race or nationality, or between the class divide of privileged and the poor; it has brought misery to the integrated world in unimaginable proportions equitably. If indeed the coronavirus was devised by the Chinese state, it would have been an economically suicidal move. Roughly five million people, by official estimates, lost their jobs in the first two months of the crisis. The Economist’s Intelligence Unit predicts that by the end of the year, livelihoods of around nine million people would be hanging by the dagger due to the financial implication on corporations. The outbreak has also renewed considerable interest in de-centralising manufacturing units from China into other parts of the world. So far, fifty-six global manufacturing behemoths have applied to shift their bases out of China into nearby East Asian economies. A country that wishes to have economic command over the global order cannot afford to drive out the very corporations that finance its growth.

At Stake: Credibility of Global Institutions

Of course, a few nations, mostly East Asian, combated the coronavirus in its early stages with proactive response to blunt the effectiveness. Others were not so lucky and thereby got caught in the crossfire of economic haemorrhage and rising deaths. India’s lockdown, although draconian and resulting in unending hardships to the populace at large, has somewhat managed to stem the surge of cases that was expected in a country as diverse and dynamic as itself. The United States has lost the battle not because the virus was explicitly ‘programmed’ to infect them, but because of widespread ignorance, foolhardiness on the part of the national administration, and most importantly, a lackadaisical attitude on the part of the natives themselves. A few days back, the mayor of Las Vegas- the supposed ‘entertainment capital of the world’- advocated the complete reopening of the casinos to pump the economy, utterly oblivious to the perils it carried.

The outbreak of the pandemic has also put the credibility of global institutions like the World Health Organisation (WHO) at stake. The WHO was accused of complacency and pliability to Chinese claims when concentrated pneumonic clusters were discovered initially in the Hubei province. The organisation indeed failed to independently test the veracity of cases, and thereby did not live up to its founding principles. It continued to vet until late January that the novel coronavirus was not a potent threat to humankind before strong evidence suggested the obverse. The United States, responsible for providing 15% of the WHO’s budget, has now stopped funding over claims of delayed action and misleading advisories. UN Secretary-General António Guterres was swift to condemn Trump’s move, saying the WHO “… must be supported, as it is absolutely critical to the world’s efforts to win the war against Covid-19.” Almost parallelly, economic and political institutions are also under severe duress during the lockdown period across the world. Rating agency Morgan Stanley expects a global recession in the first half of the fiscal year 2020-21. Fitch Ratings has slashed India’s GDP growth rate prediction to 0.8% after two stints of lockdown that have battered the economy. The political machinery is also under fire in several parts of the world, battling not just the crisis, but also negative publicity coverage detailing mishandling and inept administration. Brazilian President Jose Bolsenaro has also been heavily criticised for his reluctant stand on an emergency intervention to aid the crumbling economy, forcing provincial governors to act on their own accord. India has had considerably better instances of cooperative federalism as has always been seen in times of crises.

The Way Forward

There is not an iota of doubt that an international commission should be established to probe the outbreak of this virus. If Chinese officials are found guilty of misappropriation, they should be taken to task. However, there is no benefit to the mass hysteria surrounding such conspiracy theories at this moment. They hold no gravity unless verified and cardinally serve to promote hatred and racism towards people of Chinese genealogy. If we have integrated the world to a scale famously christened the ‘global village’, it should also be equally convenient to derive benefits of this connectivity at the lowest levels of the village. Several prominent Data and IT industry firms have already made their products open-access for a limited time to enrich and benefit whatever conclusive outcome can be derived via the use of appropriate technology. Stimulus packages need to be doled by governments across the world to kickstart their economies. As the famous American economist Paul Krugman said, it is best to “… maintain profligacy in depression, and austerity in good times“.

If the pandemic has provided us with a lesson at all, it is this- that the world is brutally unprepared to deal with catastrophes of such magnitudes. Leaders across the globe should pledge allegiance to nurture and spend on medical science and healthcare, cutting across party lines. In the twenty-first century, even an outbreak in the remotest corner of a deserted African village has the potential to bring chaos and wreak havoc on establishments across the world. The primed catchphrase of ‘Vasudeva Kutumbakam’ is what we need to recall now, allowing ourselves to heal the world and committing resources to fight the battle together- if nothing, almost as a requiem for Li Wienliang- who braved dreaded State institutions to blow the whistle on the horror that the world was soon to witness.