India’s agricultural sector has for long been the backbone of the national economy. As India emerged out of the cusps of independence, it realised the vitality of food security amidst a world battling with a heightened food crisis post the trials of the Second World War. Its leaders were doubling down on attempts to boost domestic agriculture in order to meet rising internal demand and make what was evidently the livelihood of the masses, more profitable. This sentiment is perhaps nowhere better captured than in Shastri’s iconic ‘Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan’ pitch- a phrase that still resonates today. Several institutions were established to look after the welfare of the farmer and secure the common interests of the agrarian community.

The onset of globalisation, aided by the liberalisation of the Indian economy to foreign investment and trade in 1991, permanently changed the fate of the socialist state policies that regulated Indian agriculture earlier. While new sectors such as services and manufacturing witnessed unprecedented booms, agriculture was generally perceived to be a low-return, lacklustre investment. The problem was further accentuated by the government’s unwillingness to increase public spending on promoting research to better productivity rates pan India, instead shifting a significant portion of the expectation on private bodies. In fact, the growing decline in the economic worth of agricultural products to GDP is a well-documented feature in recent times, contributing to an estimated 16% of the GDP at present, while still being the primary source of employment for over two-fifth of the country’s workforce.

Need for an overhaul

The stench of a stagnating agricultural sector was being felt with every passing year. Most of the farming in India is still done with minimal mechanisation and automation, as such capital-intensive farming is beyond the reach of many small farmers. Low productivity often meant that costs incurred during the harvest season were not recovered in totality and thus, gave rise to a vicious debt cycle that marginal farmers find very difficult to climb out of. The Situation Assessment Survey of Agricultural Households, conducted in 2013, pegged average family earnings at ₹6,426. The earnings worsen progressively from the ‘northern bowl’ to the eastern belt, with a corresponding slide in productivity. But all of these correlate to systemic deficiencies. What then, constituted the structural deficiencies?

One of the primary faults in the farm sector was a dysfunctional APMC setup. The APMC Act provided for the creation of mandis or common trade hubs, where traders and middlemen would congregate and compete to offer a better price for the farmer’s produce. These mandis were under State control and thus, provided a safe space for the farmers to sell their produce at market rates. However, cartelisation of APMCs and attempts to game the system by traders according to their own vested interests soon ensured that the farmer lost out against an increasingly manipulative system. It also shackled the farmer with several other constraints. Over the years, around 18 states have allowed private markets, 19 states have allowed direct purchase from farmers, and another dozen states have allowed farmers’ markets outside of APMC. There are less than 7,000 mandis in the country today, while various official estimates have put the required number between 10,000 and 40,000.

Another momentous challenge faced by the farming community was the decreasing size of landholdings. A rise in debt and poverty often constricted the farmer to a small patch of land. Former RBI Governor C. Rangarajan, in an editorial, expressed deep concern at the state of landholdings and noted that the average size of farmland declined from 2.3 hectares in 1970-71 to 1.08 hectares in 2015-16. At the same time, the percentage of small and marginal farmers shot up from 70% in 1980-81 to 86% in 2015-16. All of these only pointed to growing distress in the sector and resulted in tragic farmer suicides across the country over a number of years.

Past Committee Recommendations

A slew of committees has been set up since Independence to look into the issues of agrarian distress and suggest appropriate remedies. Perhaps the most eminent of these committees are the Swaminathan Committee and the Shanta Kumar Committee reports. The Swaminathan Committee report made several recommendations in five reports that it submitted to the Manmohan Singh-led government shortly after 2004. It identified the pain points of Indian agriculture, many of which surprisingly recur today.

It noted that the quantity and quality of water used in the farming process was a key factor that determined the volume and the quality of the end product. It recommended setting up facilities to ensure regular, and quality water supply to farms that require water-intensive cropping. It highlighted how low adoption of technology, used extensively in the developed world, was hampering progress. It also identified the lack of institutional credit support to small farmers that stopped them dead in their tracks onto the way of expansion and further consolidation. Some of the diagnoses done by the Swaminathan committee were looked into. Now, several credit incentive schemes for farmers, such as the Kisan Credit Card, are widely available. However, their takers are few; most shy away from the governmental support due to fear of further entrenchment in unpaid dues and the hounding that would follow soon after.

One of the principal recommendations under considerable contention today is the recommendation on the price structure of the Minimum Support Price (MSP) that the government offers the farmers whose produce is unsold at the open market. The committee recommended that the farmers should be paid a minimum support price at 50 per cent profit above the cost of production classified as C2 by the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP). C2 is the most comprehensive definition of production cost of crops as it also accounts for the rentals or interest loans, owned land and fixed capital assets over and above the actual paid-out expenses incurred by farmers.

While the Swaminathan Committee dealt with the core agrarian distress and dealt with finding solutions to those problems at hand, the Shanta Kumar Committee was tasked to improve the efficiency of the much lambasted Food Corporation of India’s policies and overall setup. As of 2020, the FCI has over 58.49 million tonnes (MT)- over a year’s worth of buffer stock- in its reserves. The FCI has been a warehouse of inefficiency for a significant amount of time. It procures millions of tonnes of annual harvest from farmers every single year across the country, but a sizeable chunk of it lay unused in its godowns and ultimately rot with passing time. The committee suggested that private players be allowed to establish a parallel storage buffer, so that food produced may not go waste- while still securing the food security interests of India. It also noted that the FCI should involve itself in full-fledged grains procurement only in those states which are poor in procurement. This would ensure that excess stock is not lodged with it, and simultaneously ensure that farmers whose produce go unsold are still offered the base prices.

Epicenter of Trouble: The Farm Laws

Back in September 2020, the Centre bulldozed through the parliament to enact three bills into permanent Acts that would radically overhaul the prevalent system of agricultural trade within the country. The three acts cardinally deal with the facilitation of inter-state agricultural trade, making contract farming more accessible to farmers, and removal of stockpile limits on certain commodities listed under the Essential Commodities Act. The triad of the three bills was passed in both Houses of the Parliament, the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha, with minimal debate and deliberation. The fact that the bills- labeled as a watershed moment for Indian agriculture- were brought into the forefront without consultation with major stakeholders stoked discontent at large.

The Farm Bills essentially attempt to set up a parallel market space for agricultural goods beyond the mandis, helping in theory fetch a farmer wider reach for his products and thereby, earn better prices for the produce. However, running a parallel market beyond the control of the APMCs has the inherent risk of pushing the MSP system into oblivion, and ultimately may lead to MSP being scrapped. Even if the government now gives an assurance of continuing the MSP system, it ultimately boils down to a matter of trust, as noted economist Kaushik Basu opines. Any dilution of the MSP setup, by exploiting the loopholes- such as offering prices much lesser than the market price and setting up of mandis at centers far apart from one another, ultimately erode the confidence in the system of guaranteed pricing.

Similarly, there is widespread fear permeating the air on the entry of corporates into the mostly untapped, orthodox agriculture sector. As aforementioned, the bulk of the farmers represent the small and marginal cultivators who are at the bottom of the economic strata. They hardly have any credible knowledge to understand the nuances of legal contracts drafted by corporate teams who obviously have an eye towards maximising profits at all costs. The laws peculiarly keep the entire dispute resolution process out of the ambit of the judiciary by appointing officers who have been vested with necessary powers. Small farmers, who barely make enough to ensure subsistence, certainly do not want to be entrapped by the hassle of babu-dom in their quest for justice.

The amended Essential Commodities Act (ECMA) toes the line of the Shanta Kumar Committee recommendations. The opposition to the amended Essential Commodities Act is that it allows for unlimited stocking of goods defined as ‘essential items’ earlier by any individual or corporation now, unless there is a situation of unchecked price rise. The Act goes on to state that stockpile limits will only come into force, only when there is “… (i) a 100% increase in the retail price of horticultural produce; and (ii) a 50% increase in the retail price of non-perishable agricultural food items.” This naturally raises eyebrows at possible hoarding and profiteering during crises. The Central government defends the amendment on the grounds that it allows a fair space to the traders and corporations that wish to purchase produce in bulk. Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh publicly castigated the Act, claiming that the amended ECMA would permit artificial price inflation and illegal profiteering from right under the State’s watch.

To assuage farmers’ hurt and to create a space for further dialogue, the Supreme Court on 12 January stepped in to stay the implementation of the laws until further orders. This also naturally meant that the earlier system of APMC trade, and MSP guarantee, would be applicable until further ruling. It also appointed a committee to suggest changes after extensive consultation with all affected parties. However, concerns have been raised after most of the panel members on the committee were found to subscribe to a certain orientation of thought, thereby violating a fundamental constituent of mediation: those who mediate must harbour neutral views on the issue of contention.

A Lens on Reality

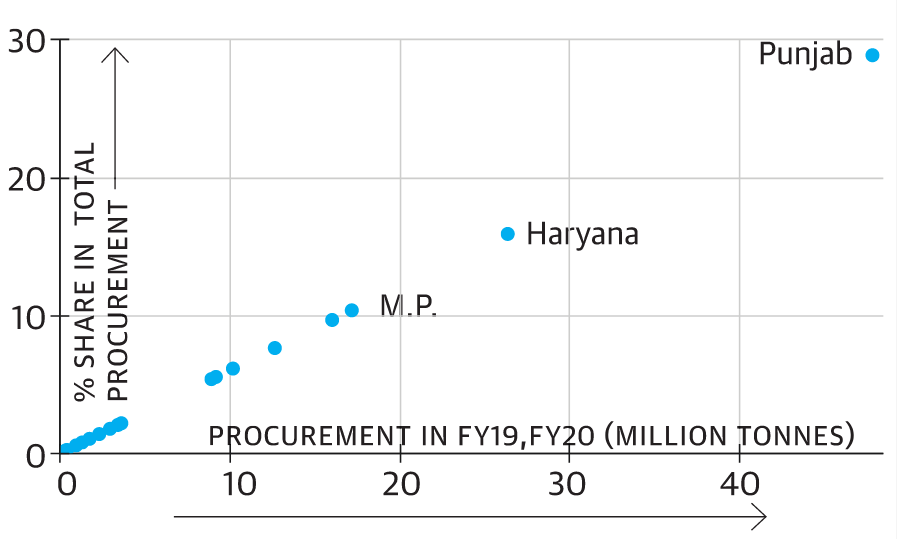

To better understand the root cause behind the massive protests that even transcended the borders of India, it would be helpful to evaluate and derive inferences from surveys and data already available with us. In the last two years (2018-2019), approximately 45% of all the rice and wheat procured by government agencies came from just two States – Punjab (28.9%) and Haryana (15.9%). M.P. was a distant third at 10.4%.

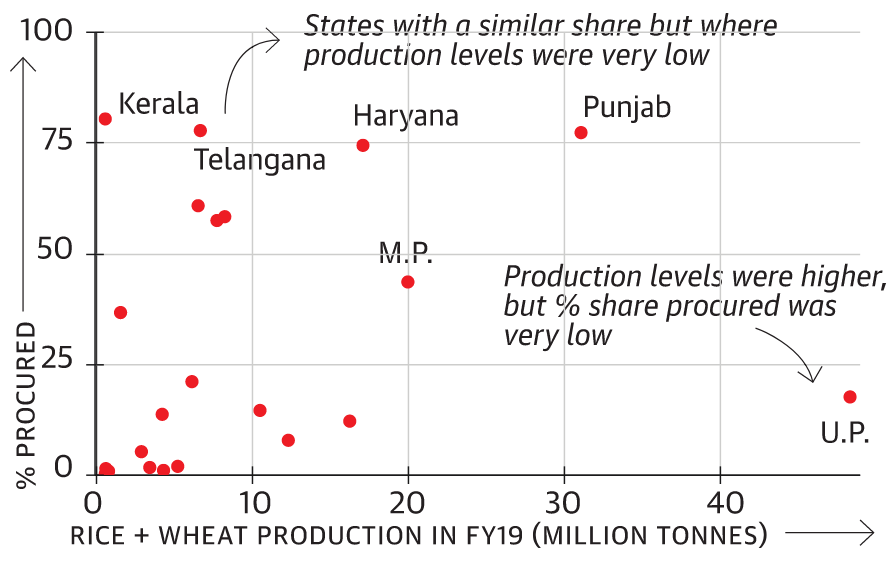

Taking a close look at procurement figures from individual states, we again find a similar pattern of high government procurement from Punjab and Haryana- two states that have been the epicenter of protests- while other states have lagged behind significantly. The procurement figures, from FY2019, reveal that government agencies procured close to 75% of all wheat and rice produced in the two states.

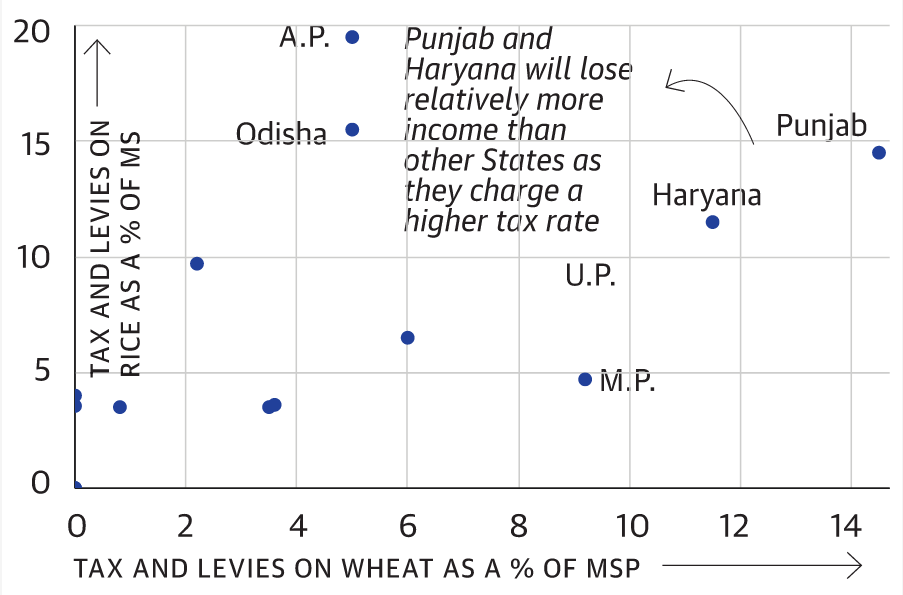

Even beyond the farmer, the state governments of Punjab and Haryana stand to lose significantly on taxes levied on food procurement at government regulated mandis if the farmer opts to sell their produce outside the ambit of the state’s setup. Both Punjab and Haryana have high taxation rates on wheat, based as a percentage on the offered MSP- between 11 to 14%.

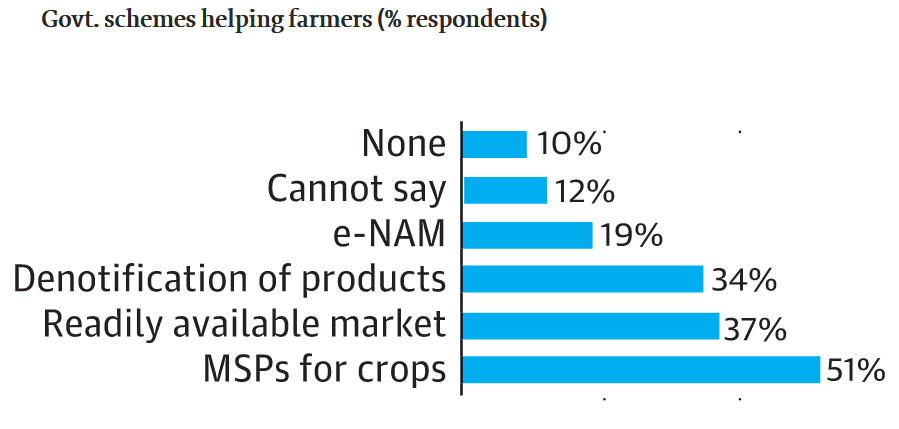

In a 2018 RBI survey, more than fifty percent of farmers who participated articulated their support for the MSP regime to continue. They were not very much bothered about the intermediates and middlemen that the present Farm Laws intend to eliminate.

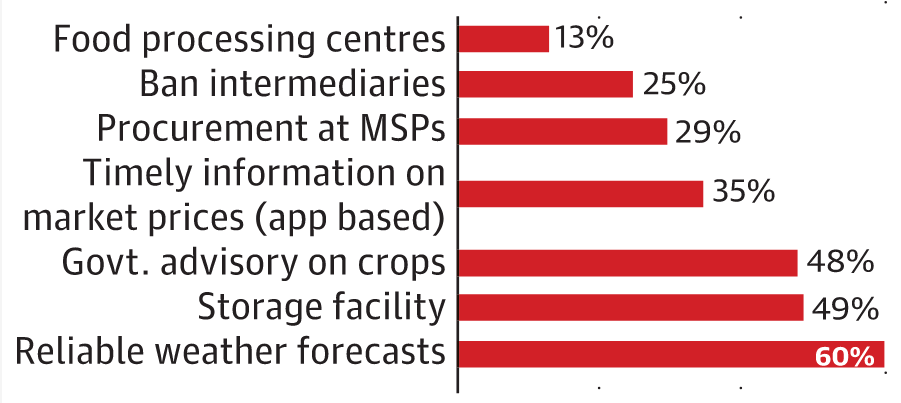

The farmers also identified better access to storage facilities and reliable weather updates from the IMD as factors that help them towards realising better prices on their share of crops, over the concern of interference by middlemen.

Adopting a Three Dimensional Approach to Farming

India’s agrarian sector is intricately woven around the triumvirate of price, productivity and public policy. Take any one of the three constituents out, and the ramification can be a devastating blow on the stability of the farm sector.

Price has always been a key issue because it the singularly most important metric that determines the profit ratio of the farmers. If they are getting good prices from the market, there would not have been any support for the MSP regime. However, the volatility of the open market drives home the question that in case of non-procurement or poor prices offered, does the entire produce go waste? The MSP system acts as a cushion that protects farmers against such negative price shocks. Dismantling it would throw many small farmers into a tizzy. At the same time, the government cannot indefinitely continue to procure all unsold produce as MSP. Market Intervention Scheme and Price Support Scheme (MIS-PSS) and Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Yojna (PM-AASHA) – the two schemes that ensure the implementation of MSP – have seen a continuous reduction in the last two years. The allocation under MIS-PSS fell 25% and under PM-AASHA it came down to a mere ₹400 crores in the budget 2021-2022 from ₹1,500 crores earlier.

Consistently low productivity rates across most parts of the country, barring the more prosperous agrarian states of Punjab and Haryana, continue to act as a major deterrent towards expanding India’s potential in this field. Governmental support and spending towards adoption of latest technology need to be adopted at the earliest. The Indian Government has also entered into deals with Israeli firms to deploy advanced agricultural techniques onto Indian farms to observe the promises it holds for India’s future. However, for adoption of technology to be successful, the consolidation of small holdings is a must.

Public policy is the third pillar that needs to be geared in a direction that bolsters both the price and productivity prospects for the ordinary farmer. Several well-meaning laws have not been implemented due to populist whims. Now that India has a law dedicated to bringing in contract farming for the masses, we need more safeguards against the vagaries of the corporate honcho. Corporatisation of agriculture, despite its risks, can help improve productivity by a factor of two or more- because in such cases, the company shall reason in the input costs that employ better fertilisers and techniques for growing the crop as desired by the company. By drafting the right legislation and in the right tone, the government can inspire a lot of confidence even among ambitious, next-generation farmers who wish to step into modernised farming but are held back by distrust and suspicion.

A Road Ahead

India’s recently introduced farm laws are forward-thinking, visionary, and are the need of the hour. There can be no denial that the Keynesian concept of animal spirits has to be urgently imbibed into the fledgling agriculture sector on account of a host of troubles it faces today. Unless the floodgates of investment are opened to the sector at large, India’s agricultural output will continue to remain plagued by the issues that bother it at present.

The primary agenda of the farm protests, demanding the complete and unconditional repeal of the laws, is somewhat problematic. The emphasis of the protests should be rather directed at safeguarding the rights of the farmer through definitive, water-tight legislation that allows the farmer to freely interact with the new variables that shall come into play once the laws are deemed operational again. It is high time that the government looks to patch the grey areas of the laws- and thereby build a better farm sector- than engage in indirect favouritism of corporates and thereby test the sentiments of the farmers. India’s farm laws are a turning point for the farm sector- but the right message needs to be delivered to capitalise on the immense promises it offers.