The annals of post-modernisation history have shown us that very few parameters can go on to substantially alter the course of a national landscape than definitive education. Right from the tenets of preschool education to contemporary higher education and beyond, the twenty-first-century world is governed by the barometer of knowledge. Hence the establishment of world-class infrastructure, coupled with an enabling environment conducive to holistic education, has always been the desirous way ahead. The Draft Education Policy (2019), despite its fair share of controversies, had harped on several promising suggestions to better the disjointed education system, and parallelly tried to iron out irregularities as far as practicable. Its successor, the New Education Policy 2020, seems to have hit the right note.

The NEP 2020 comes jam-packed with a lavish spread of many sought-after reforms, with a particularly strong emphasis on the universalisation, quality, and a skill-based approach for the all-round development of a child’s cognitive and vocational abilities. It would indeed be safe to say that amidst times of uncertainty and many an adversity, the roll-out of NEP is a harbinger of positivity, and at the least, reassuring on several fronts. This article shall attempt to dissect certain aspects of the NEP under the microscopic lens, evaluate the policy measures taken, and ultimately discern a roadmap for India to glide onto the shore of success.

High On Intent

The cardinal thrust of the New Education Policy, rekindled after thirty-four years, appears to be on the universality of education. The policy includes within its ambit not only those left bereft of free state-sponsored education beyond the age of fourteen, but also promotes societal inclusiveness by making a special note of the needs of the differently-abled. Earlier, the Right To Education Act made it mandatory for children falling within the age gap of six to fourteen years to have primary school education for free. While the intent was good, not many beneficiaries were interested in continuing their studies beyond the requisite period. The present proposition to extend free schooling until the age of eighteen will certainly incentivise the continuance of education for those who are bound by financial constraints. Data from the DISE portal also corroborate the necessity of the move, as is illustrated by the chart attached below.

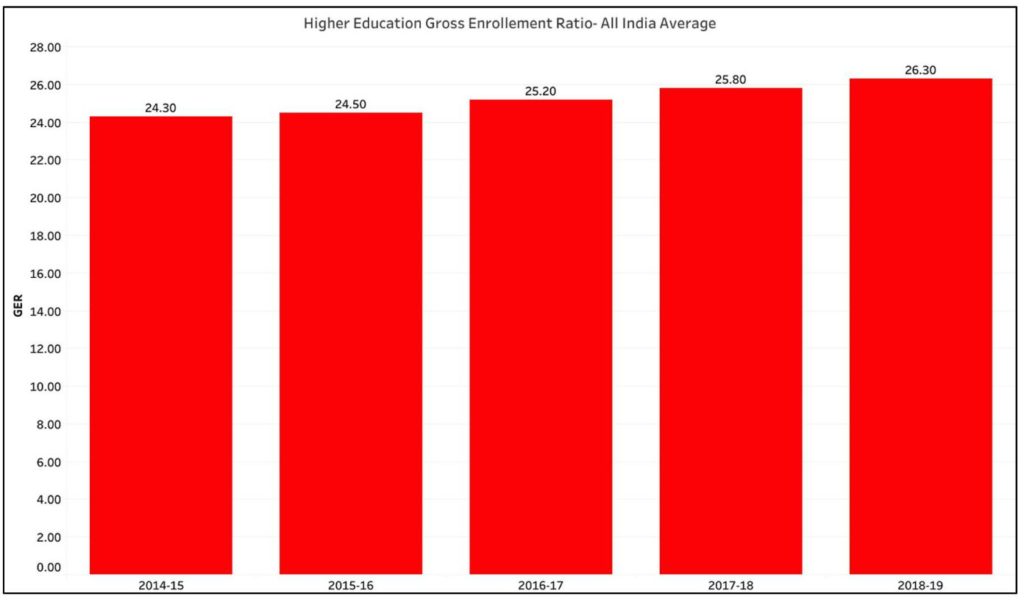

In light of the said objective, a vision to achieve the target of 50% Gross Enrollment Rate in higher education has been set for 2035. As per statistics unveiled by AISHE, India recorded a 26.3% GER in 2018-19. Parallelly evaluating the year-wise GER rates makes it evident that the task ahead is akin to that of scaling a mountain, and any laxity or complacency may disrupt the sanctity of the efforts. Furthermore, alongside infrastructural support, sharing of school premises for other enriching activities has also been suggested to make the maximum utilisation of available resources. To further the cause of inclusive education, a gender inclusion fund has been set up, and Special Education Zones have been demarcated. Attempts are underway to make the process more equitable, as GER shows significant deviation when contrasted to the General-class population versus those in the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes category (21.8% and 15.9% respectively).

Another aspect of the revamp that the NEP brings with it is the approach towards multidisciplinary education. India’s attempt to introduce such dynamism and flexibility of choice in choosing subjects earlier had mostly been met with distrust and scorn at the highest levels, leading to such an approach being shunned for long. One of the prime reasons for India’s top universities failing to compete with the best in the world is a lack of voluminous interdisciplinary research work. The new policy focuses on the preference of the individual rather than mass tendencies, aiming to offer the student complete freedom on the choice of subjects. This shall take shape right from the present Grades 11 and 12- where the rigidities of the three domains of Science, Commerce and Humanities shall cease to exist, and the student will have a choice to study an amalgamation comprised of the best of each stream. The government also talks about the establishment of MERUs- Multidisciplinary Education and Research Universities- which will be accorded the same status as that of IITs and IIMs throughout India.

In sync with the pedagogical updates, the policy also effectively narrows down on honing the skillsets of the teachers. It formulates mandatory standardisation by requiring a minimum of four-year integrated B.Ed course to be eligible as a teacher. Direct recruitment, as well as private practise, will only be permitted after clearance of the centrally-conducted TET (Teacher’s Eligibility Test). It is a sensible move as it addresses the concerns of woeful teaching standards at the grassroots level head-on. By providing opportunities to the better-abled, the teaching profession will witness a natural shift from disinterested, underpaid faculty to well-qualified, motivated and well-paid staff. Hence, this will also have a recuperative effect on the learners, whose learning rates are expected to shoot with better teachers and an improved pedagogy in place.

Economics Speak: A Statistical Purview

Past studies on the importance of formal education have often indicated strong correlation between the average level of education and the national growth rates. These ideas were consequently explored by several economists in detail. One among them was Nobel awardee Robert Solow, who was the first to note that a country’s production function was dependent not only on capital inputs and labour, but also on pre-existing Human Capital (Total Factor Productivity). It was later expanded on heavily by Paul Romer, the 2018 winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, who said that it is technological advancement alone that is responsible for the “endogenous growth” of a nation. This endogenous growth was critical to securing a long-run sustainable growth pattern, he endorsed. Today, most of the world’s developed economies are knowledge economies, and the rest serve as ‘assembler economies’. India, unfortunately, falls in the later bracket, being plagued by low literacy rates and poor development of human capital. In the inaugural report on ‘Human Capital Index’ launched by the World Bank in October 2018, India was ranked at the 115th position out of a total of 159 countries that were evaluated. The NEP capitalises on this distinct void and seeks to fill the vacuum at the earliest.

India’s spending on R&D, a key determinant of scientific advancement, has remained historically low at 0.6-0.7% of the GDP. The New Education Policy promises a renewed thrust in public spending on education by the government, to the tune of 6% of the GDP. This figure was originally quoted by the Kothari Commission constituted in 1966 to look into the issues concerning education in India’s nascent stage. Yet, due to political negligence and bureaucratic red-tape, its implementation had never been prioritised and thus, was rescinded to the alleys of yore. Solow’s and Romer’s ideas on growth being a function of the human capital- and thereby indirectly- public investment on education can be crisply represented on a logarithmic scale. I also went ahead and compiled HDI data and their corresponding public spending on education for nine countries at random, and found a linear correlation that grows more exact with more number of input samples.

An increase in public spending on education also has an inverse relationship with Maternal Mortality Rates (number of deaths of mothers per 100,000 live births), as would be ordinarily desirable. By employing a power regression pattern onto available data from a finite set of countries demographically spread out, the trend is evident:

Ambiguities Remain: Problem Spots

However, not all is merry and blue. The NEP policy framework has multiple occurrences of ambiguities and is laden with contradictions at times. For example, despite the running refrain of autonomy and freedom of the choice of subjects towards the end of primary education, the vocational subjects will be defined and limited by ‘states and local communities and as mapped by local skilling needs‘ (NEP 4.8)- and not left to the choice of the students. Secondly, the NEP emphasises on the enhancement of vibrant campus life for a better teaching-learning process. Yet, legal safeguards for promoting open thought and permitting a greater degree of freedom of speech within the campus walls have not been secured. Thirdly, one of the most widely-picked up takeaway from the announcement has been the proposed ramp in public investment to 6% of the GDP annually. Yet, statistics tell us otherwise; our spend to GDP ratio has actually been falling. During FY2012-13, education expenditure was 3.8% of the GDP. It fell in 2014-15 to 2.8% and registered a further drop to 2.4% in 2015-16. Thus, while the world average mostly remained constant, India’s public funding reduced drastically in the same period. While the vision to improve the spend to 6% is commendable, it is to be seen how far this can be executed- especially at a time the Government of India is suffering from a budgetary crunch.

Fourth, the establishment of anganwadis in the hinterlands was set up with an explicit purpose to look after the health and nutrition of children and newfangled mothers. To depute the task of education, and to seek deliverable outcomes from them at periodic intervals puts an additional burden on the already stretched anganwadi centres. Personnel in anganwadi centres are primarily healthcare workers and not trained teachers. Unless the concern is immediately addressed, it may result in a shift of focus from nutrition to early education alone, which may have devastating consequences in the long run. Fifth, in an attempt to solve the language controversy that erupted last year, the NEP advocates the medium of instruction as the state language or the mother tongue up to the fifth grade. What after grade five? How would the students cope with an intermediate standard of English- which is what they will be exposed to mostly in higher education? Education remains put in the concurrent list- meaning both the State and the Centre, can legislate. Although Constitutional provisions allow for Central laws to ride roughshod over state laws when they conflict, would it be right to bypass state laws that cater to regional requirements? And lastly, it must be ensured that in an attempt to ease the burden on students, academic integrity is not diluted: in other words, fundamentals and concepts required in higher classes must be dealt with as seriously as was done in earlier years. Students must not land in a muddle because of the availability of plentiful options.

Concluding Thoughts

The National Education Policy 2020 is big on promises and goals. To re-imagine the entire construct of the present educational system and work on suggestions collected over five years preceding its announcement is a feat in itself. Clearly, herculean efforts have been put into the making of this document. If the NEP works well, it will have the spellbinding effect of revitalising India’s distraught- and disbanded- education system into the cusp of academic heights again. The opening of gateways for foreign universities to enter the Indian landscape should not be a source of worry. My personal take is that they would serve to be excellent sources of competition for domestic universities and privately run colleges, thereby ensuring welcome healthy competition.

However much be the strong intent, the true success and impact of the NEP can only be gauged when the policy delivers on its core vision. For that to happen, the ambiguities pointed out must be immediately sorted out; and execution should only begin when the document is crystal-clear. Ravish Kumar, while accepting the Ramon Magsaysay award last year, had spoken of India’s growing knowledge inequality as a deterrent to the growth potential for India. He called for an overhaul that would rest on the pillars of universality, inclusiveness and skills-based education. The NEP is in sync with his, and many other educationists’ point of view.

The National Education Policy 2020 has hogged all the lights and is ready for a perfect reception. The audience is already prepared. We only await the action.