The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc across the world, not only with its sheer magnitude of suffering and loss, but also has successfully managed to bring otherwise resilient economies to a grinding halt. This has had widespread ramifications on the workforce in general, and has been amply magnified for the neglected strata of the society. The CMIE’s estimates on unemployment shot up from 8.4% in mid-March to a whopping 23.4% in the present day. Thus, ameliorative steps, both fiscal and monetary in nature, are the need of the hour.

At this critical juncture, it is essentially a gamble on predictions and forecast. But to sit idle is not an option at all. Fiscal policies are clearly more effective in dealing with a pandemic situation. On the fiscal front, the government has a smorgasbord of options available on its platter. Most advanced economies have adopted a relief package worth 10% of their GDP. In contrast, the GoI has drawn up a plan that expends ₹2 lakh crores for immediate relief only, estimated at 1% of the GDP. An urgent need is to increase the transferred sum to a more sustainable figure, around ₹7000-8000. This may have the effect of inflating the fiscal deficit, but a deficit should be the least of worries in times of crises. KPMG’s report on the impact of COVID-19 in India suggests consumption figures will be the worst hit. Hence, an effort may be made to reduce the personal income tax rates for the time being, so that people have money in their hands to spend on once the situation improves. This will also have a stimulating effect on the economy, by creating a demand surge. The Centre can also further slash the corporate tax, thus aligning it with the East Asian models, which will propel a tendency to invest on part of the corporates. Further, the government can also extend the deposit date for advance tax by a period of six months, which will help crucial sectors as MSMEs to deal with reduced operating margins.

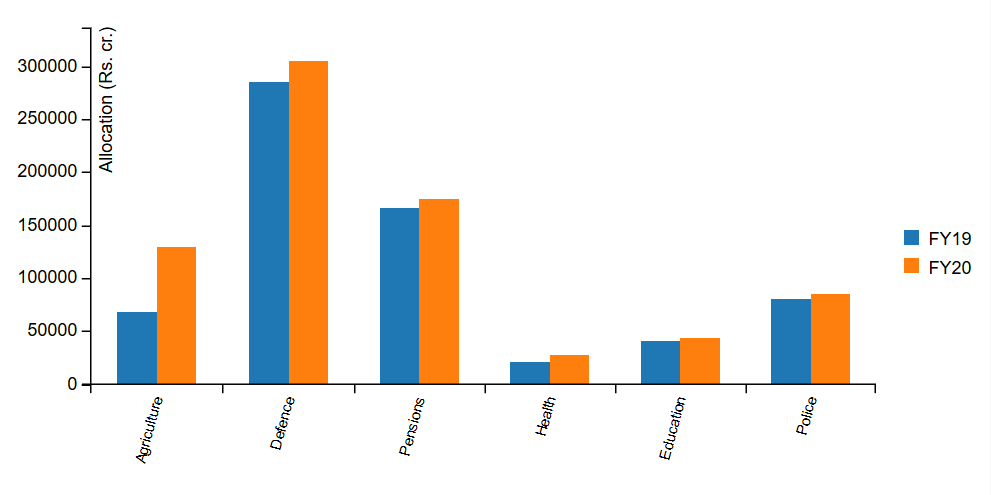

Inflationary worries, particularly on foodgrains, can be curbed by utilising the surplus stockpile available with the FCI. Naturally, greater supply of basic food items through the PDS system, therefore, should also be a focal point. A massive prop in healthcare allocation is also necessary on an immediate front. The Centre’s own National Healthcare Policy envisages a spending of 2.5% of the GDP on health infrastructure, but the present allocation of around 1% of the GDP considerably languishes behind the objective. The Centre now has the added responsibilty of identifying critical sectors, such as auto, pharma and telecom with reliance on global supply chains, and work strategically to bring down foreign dependence by building alternative options. An extension on payment of AGR dues by the government may also be filed for the consideration of the Supreme Court, to assuage the telecom industry’s valid concerns for the time being.

On the monetary front, the RBI’s intervention to dramatically slash rates by 75 bps will have a positive effect on credit availability in the market. However, it is to be noted that monetary policy will have a very little impact on anchoring the economy. While a monetary policy is hugely influential in addressing demand shocks, it appears quite blunt while dealing with supply-side shocks. Thus, a rate cut can have at best a transient effect on market sentiments, but guarantee nothing in permanence. Not all is lost, however: a three month moratorium period extended by the RBI to all EMI debtors will have a beneficial impact on driving consumption higher. Similarly, a slash in CRR requirements and reverse repo rates will ensure that banks have more money to lend with them, and ensure that expansionary tendencies are not curtailed due to a lack of credit.

The COVID-19 crisis brings with it an opportunity to reflect and bring about structural changes in the economy. It solidifies the belief that dependence on China as the global manufacturing hub can no longer be relief upon. Resilience from external supply shocks can only be compensated if localisation of key sectors is worked upon. The lockdown has also brought about a massive adoption of digital technologies, which is a welcome development. Furtherance of Digital India-centric policy can help aid recuperating businesses and industries. It has also proven how important it remains for the corporate to be financially prudent and conserve cash – as a buffer measure- to effectively steer itself out of unpredictable times as these. India can present itself as a viable alternative for the hub of global manufacturing. Can our policies step upto it?